No, You Don't Have to Take Eight Showers a Day to Be a Great Writer

Not everything your heroes do explains their success.

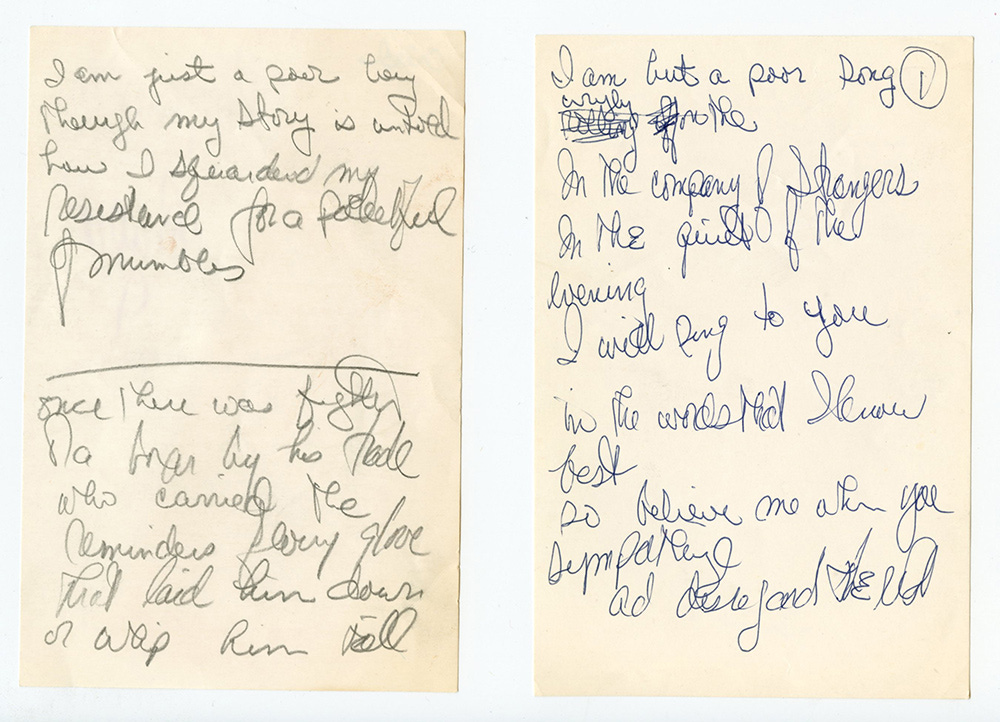

It is my opinion that Paul Simon is the greatest songwriter of all time.

As far as takes go, that’s not a particularly hot one. He’s one of the most acclaimed songwriters in popular music history, from his work in Simon & Garfunkel to his later solo albums like Graceland and (my favorite) The Rhythm of the Saints.

Back when I was a young songwriter trying to make a career in music, I listened to Simon’s music obsessively. When that wasn’t enough, I started looking for every interview I could find in which he discussed his process.

What I discovered was that Paul Simon writes very slowly. He has said in interviews that he’ll spend four to six weeks to finish writing a song if that’s the only thing he’s doing. If he’s not working steadily, it can take him four to six months to finish a song. He’ll go through fifty pages of a legal pad just to develop the lyrics.

Simon’s process, and the incredible creative and commercial success that it’s brought him, is proof that when it comes to creative work, slow and steady is best.

Except it’s not that simple.

Because there’s another Paul. Paul McCartney. Another one of the greatest songwriters in the history of music.

And how does Paul McCartney write?

Very, very fast.

McCartney likens his process to “doing a crossword puzzle.” He says he’s “of the school of the instinctive.” When asked about the secret to his songwriting success, he quotes the poet Allen Ginsberg: “first thought, best thought.”

McCartney wrote “Hey Jude” while on a drive in the countryside. What about “The Long and Winding Road”? Did he take a long and winding road to write it? Here’s him describing its origins:

“I just sat down at my piano in Scotland, started playing, and came up with that song.”

McCartney is the anti-Simon. He would never spend 50 pages of legal paper to develop a lyric. First thought, best thought.

So the question is: if you want to write great music, whose approach do you follow?

Or maybe that’s not the right question at all.

A fulltime writer whom I deeply admire recently posted about how she spends the huge majority of her work time reading, and a much, much smaller percentage actually writing. She encouraged aspiring writers to do the same. “Most of writing is reading.” It’s great advice — if you’re the kind of person who has lots of time for both reading and writing, and for whom inspired writing requires a thick, constantly flowing pipeline of new inputs.

For others, a short daily reading habit in service of a much longer daily writing session might be best. Or maybe something in the middle. For me, I find that as long as I’m reading something, for some amount of time, every single day, it reflects well in my writing. Others might find something completely different. For some, revolutionary as it sounds, most of writing is… writing.

Or maybe most of writing is taking showers.

The Oscar- and Emmy-winning screenwriter Aaron Sorkin has said in interviews that when he’s working on a script, he takes as many as eight showers a day. He even went so far as to install a shower in his office for this purpose.

“I find them incredibly refreshing, and when writing isn’t going well, it’s a do-over… I will shower, change into new clothes and start again.”

Sorkin stops short of recommending this habit to aspiring screenwriters, but that surely doesn’t stop his admirers from reading between the lines. Should anyone who wants to be the next Aaron Sorkin also take eight showers a day? Or maybe it just means you should find your own “reset” habit to use eight times a day.

Of course you shouldn’t. Or maybe you should. I have no idea. I’m not you.

The takeaway from Sorkin is the same one you’ll find at the root of any successful person, in any field, if you dig down to the foundation: successful people work deliberately on the things they want to be successful at doing. They they deliberately search for and find the things that help them work deliberately, and then they deliberately do those things.

That simple idea is unbearably boring, and ridiculously vague, and just so happens to be true.

An anecdotal example: I’m a deeply distractible person. For me, the key to a successful writing session is to literally forbid myself from shifting gears or stepping back from my work until a predetermined period has elapsed. Allowing myself the freedom to do any sort of “resetting” eight times a day, let alone a full shower and change of clothes, would be inviting ruin on my focus.

In fact, I have made a rule for myself that I’m not allowed to break for lunch until I get to a point where I would feel comfortable ending my workday right then. That’s how intense my distractibility is. If I step away to make myself a sandwich, there’s no guaranteeing that I’ll ever get back into a headspace where I’ll get anything done. The result is that after breakfast in the morning, I often won’t eat until four in the afternoon.

So if you want to run a copywriting business, write a small newsletter, and teach at an Australian university, the key is not eating until 4pm.

I’m kidding, obviously. That would be ridiculous advice. For many people, it would be downright unhealthy.

But adopting my approach because you might happen to like my work is no more ridiculous than slavishly following the daily habits of our heroes. Because where does it end? Let’s say you’re a writer, and your favorite writer in the world says they write first thing in the morning, right after they wake up, because that’s when they’re freshest and most creative. That seems like a reasonable habit to emulate, doesn't it?

But then what if that same writer says they take a two-hour nap at lunchtime every day. Okay, I mean, that’s a little unusual. But they are your hero, so why not give it a shot? Uncommon success requires uncommon approaches.

But don’t forget, that writer also said they eat lots of sugary food anytime they want to, because cravings distract the brain from big ideas. And they have three whiskeys a day. And they’ve never married because relationships stand in the way of true creative independence.

Which of those behaviors do you emulate? Which ones do you ignore? Which ones do you determine are responsible for their greatness?

You quickly begin to realize that all people everywhere are a collection of habits, and the specific details of those habits tell you a lot about their personalities and values and often very little about what makes them great artists or achievers.

So does all this mean that I think the entire self-development genre is garbage? After all, isn’t the concept of self-help centered around identifying and developing specific habits? What are all those motivational Instagram accounts and bestselling books for?

They certainly have value. At least, I hope they do. I feast on those kinds of books.

Take Stephen R. Covey’s eternally bestselling 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Let’s take a look at the seven “habits” he endorses, shall we?

1. Be proactive

2. Begin with the end in mind

3. Put first things first

4. Think win-win

5. Seek first to understand, then be understood

6. Synergize

7. Sharpen the saw (Make time for renewing activities)

Could these be any more general? Keep in mind, I love 7 Habits. It’s a wonderful book. But let’s just rephrase those habits to highlight how vague they really are.

1. Do things

2. Plan to do things

3. Do important things before unimportant things

4. Don’t do things that hurt other people

5. Listen to other people

6. Work with other people

7. Relax sometimes

Those aren’t habits. Those the basic behaviors of a functioning human being. Covey’s book has become one of the bestselling self-help guides of all time despite its vague generalities because it’s a well-written, inspiring reminder to be deliberate in the way we work, interact, plan, and behave.

It reminds us of the basics we already know.

I read that book when I was around fifteen years old, and in my opinion that’s the perfect time to read it. It’s a beginner’s guide to being a functional adult person in society. Beyond that, it doesn’t offer anything all that prescriptive. The entire book could be summed up in two words.

Be Deliberate.

The simple fact is that there are no strange, unexpected, esoteric “habits” that generally guarantee success. The people we admire, the people who achieve greatness in the fields we pursue, all got there by following completely different paths — but they each followed a path. What matters isn’t their habits, but that they had habits at all.

So why do we obsessively investigate every minute detail of our heroes’ daily routines, searching for the secret to their success? Why do we jump from trend to trend, from ice baths to meditation to task batching to ashwagandha?

Because it’s simpler.

Treasure hunting for game changing habits is simpler than spending years figuring out what kind of person you are, and what type of work life is best for you, through an ongoing, deliberate, and self-aware process of trial and error.

If you’re an ambitious person with a limited number of hours in the day, it’s easier to just look at what your heroes do and copy that. But this often just leads to frustration. When their habits don’t fit on you, you start to wonder if maybe you don’t have “it” in you, that magical potential for greatness.

“My hero did X to become great, but when I do X it just makes me miserable. That must mean I’ll never be great.”

The difference between successful people and unsuccessful people isn’t found in the details of their day planners. It’s in their self-awareness, in knowing whether they’re the kind of person who would benefit from a day planner in the first place. They figure out what works for them, and they do that thing — even if it’s weird. Even if it’s not weird, and in fact incredible banal. Even if it’s something none of their heroes would ever dream of doing.

I don’t know who Aaron Sorkin’s screenwriting idols are, but my guess is that they didn’t take eight showers a day. Meanwhile, some of my favorite writers rely on habits that horrify me, just as I rely on habits that I’m sure would horrify them.

I often tell students in my songwriting classes that “it’s not interesting just because it happened to you.” My point isn’t that they have boring lives, or that they shouldn’t mine their personal experiences for inspiration. But the difference between a journal entry and a creative work is the deliberate pursuit of quality. It means that it’s not enough to put your thoughts and feelings to music. You have to be critical of how those thoughts and feelings come across. People want art to be “real,” sure. But more than that, they want it to be good. Great artists all go about their art in different ways, but they’re all deliberate in their process. They know their strengths and weaknesses, because they’ve taken the time and made the (sometimes uncomfortable) effort to develop a deep understanding of themselves.

So if you want to study your heroes, go for it. But do it for motivation. Do it for entertainment. Don’t do it so you can mimic their process. Not everything your heroes do explains their success.

If you want to be great, the person you really ought to be studying is you. Because the best approach to achieving your vision is the one that suits you best.

In other words: the only habit that really matters is the habit of developing habits.

Everything else is just info for your Wikipedia page.

What about nine showers though?

THIS IS SO GOOD. I love reading about other people's creative processes, mostly to see if there's something that I hadn't considered, that I can try. But yes, as you say, the important part is being deliberate about it. "Did this work for me? Could it work better? Did I hate every second because it's not for me or because it IS for me, but when I get better at this?"