What Gandhi Would Think About the Word "Moist"

Or how to take in new ideas and and still remain yourself

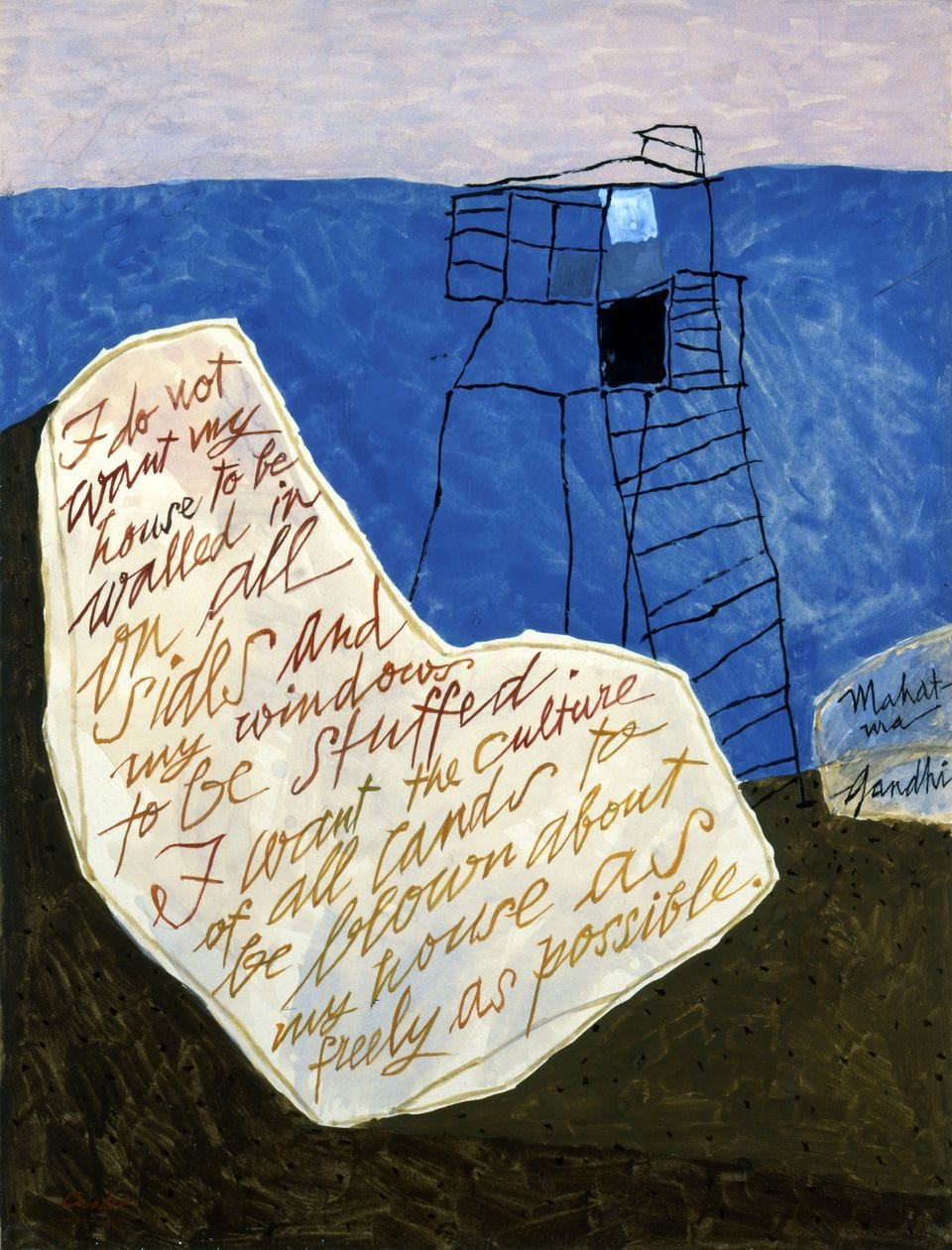

There’s a popular quote by Mahatma Gandhi that you might have heard or read:

I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible.

This is a lovely and vivid metaphor. It speaks to the idea that we all have something to learn from each other, and that the blending of cultures, backgrounds, and schools of thought can benefit us all if we open ourselves up to them.

This quote is even featured in a work by the Polish painter Hans Laabs, in his series Great Ideas from Eastern Man. It’s been displayed at the Smithsonian Art Museum.

Unfortunately, Laabs’ painting leaves out the last line of Gandhi’s message, the clause that turns what would otherwise be a pleasant metaphor about shared human cultures into a much more complex and powerful idea about what it really means to let yourself be influenced.

I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.

Gandhi was speaking in particular about cultural influence. An anti-colonial activist who proudly believed in the essential future of India as an independent nation, he was far from a utopian believer in a borderless world. He had seen the bare face of British imperialism close-up. Anyone who’s had an empire march into your nation and demand your people adapt to their way of doing things, or stolen your people as forced labor, can hardly embrace unchecked globalism.

In the metaphor of the windswept house, Gandhi was talking about cultural identity, and how the sharing of cultures can benefit us all if we never lose track of our own.

This semester I’ve been teaching courses on music and songwriting to university students, trying to communicate the idea that the ultimate goal as an artist is to not only sound good but to sound like you.

On the first day of the course, I like to write this Miles Davis quote on the whiteboard:

You have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself.

Like Gandhi, Miles Davis was talking about influence — not cultural influence, but artistic influence.

He was saying that as unique as each person is, what first comes out of us usually isn’t unique at all. It’s entirely derivative. When we’re first starting out as artists, all we have is imitation. It takes years and years of deliberate practice to combine all of that influence into our own unique voice or personal style.

Listen to Miles Davis’ early work, or the early work of almost any great artist, and you’ll usually see their influences laid bare. It’s only later in their development that their style becomes entirely their own.

Both Gandhi and Miles Davis understood something about the power of ideas, particularly the ideas of others, and how those ideas should (and shouldn’t) be used to shape our identities.

Over the last several years, our world has been given a stark reminder of how powerful and dangerous ideas can be. In America, we’ve watched as one simple idea — that the election process on which our entire democracy is based cannot be trusted — was repeated by a charismatic liar and led to an insurrection at our nation’s capital, followed by the first-ever instance of a former president being charged with what basically amounts to treason.

Before that, there was the pandemic — which saw us all confronted by a range of ideas about where it came from, how best to deal with it, and just how bad things really were.

Today, we’re asking computers to give us our ideas. As the implications of this set in, we’re beginning to ask more and more questions about how those computers decide which answers to send back to us.

When you look at recent history, it’s not hard to see why many of us have become skeptical of ideas, of the concept of being influenced by other minds. People can lie, after all. And even more terrifying, they can say something false with the conviction that comes from believing it’s the truth.

What can we trust besides our own minds, safely cloistered inside our skulls, protected from outside influences until we open the window to let them in by reading, listening, or watching what other minds have to say?

What can we learn from Gandhi and his windswept house?

That ideas cannot hurt us, at least not on their own. Any power they have comes from the power we give through our use of them.

In that way, ideas are a lot like words.

In isolation, words have no power to help or harm. It’s the way we choose, combine, and use them that imbues them with kinetic energy.

So when we’re deciding how open we’re meant to be to new ideas, I suggest thinking of them the way we think about words. Taking in new ideas simply means adding to our idea vocabulary. If we’re solid in the foundations of our beliefs, simply hearing a new idea won’t shake those foundations. It will be like a breeze blowing through the open windows. It won’t knock you off your feet. It might just carry something exciting and new into your home.

The word “moist” is famously one of the most commonly hated words. If you’re the kind of person who can’t stand the sight or sound of moist, you probably wish you didn’t even know it existed. But does knowing moist exists, and what it means, make you any more likely to use it? No. At some point your brain acknowledged the existence of moist, logged it in long-term memory, and decided: “No, I don’t think I’ll be needing that one any time soon.”

When Gandhi talked about a house with the windows open, he was talking about the freedom to take in ideas, not a requirement to adopt every idea to which we’re exposed.

If you’re a person of faith, exposure to scientific ideas about the origins of the universe don’t have to frighten you. If you’re an atheist, studying the best and most aspirational bits of world religions won’t cause you to relinquish your Rational Thinker card.

And as long as you’re aware of bias and willing to fact-check, exposure to ideas from the opposite end of the political spectrum might just broaden your understanding of a complex issue.

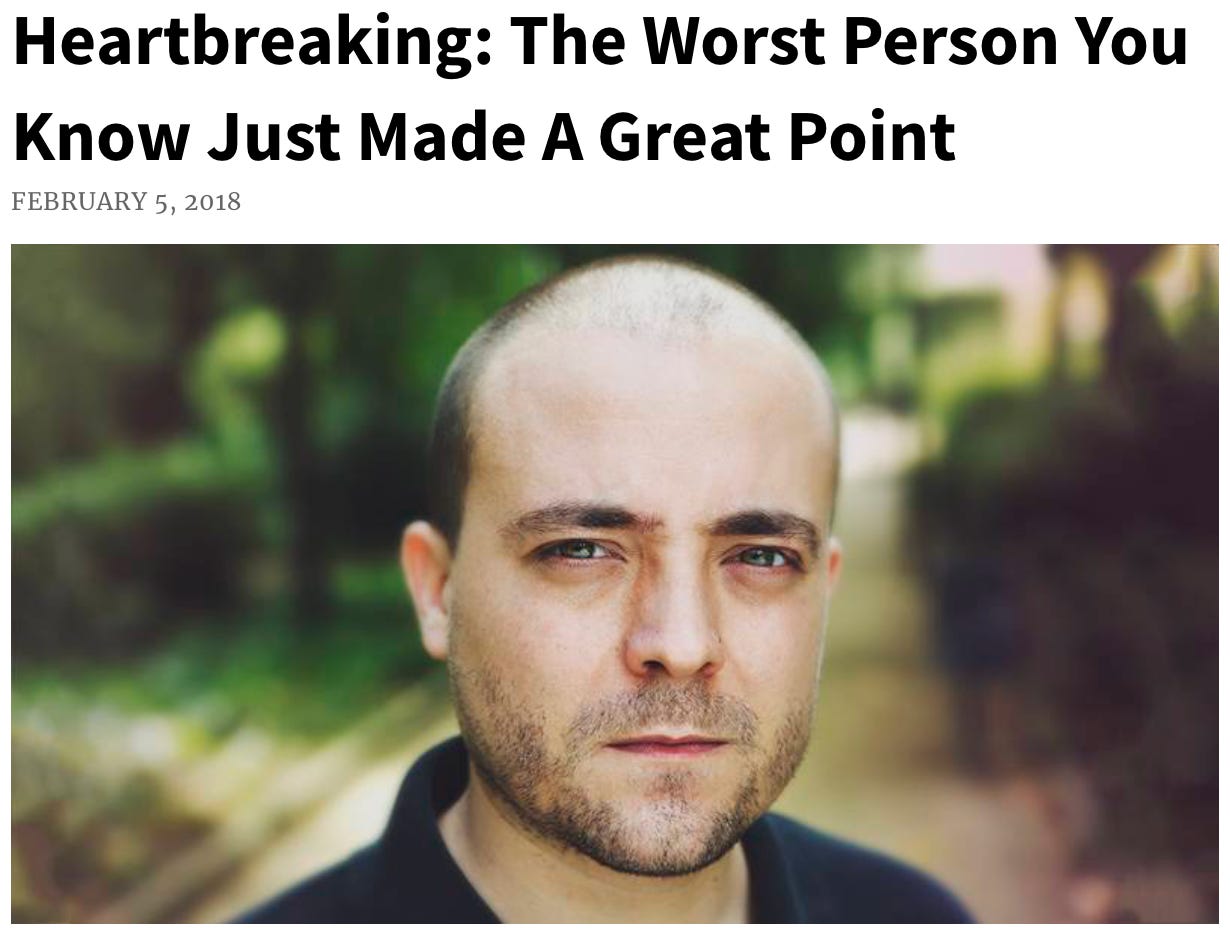

To that point, may I take a moment to share one of my all-time favorite memes:

Having originated on the satirical listicle site ClickHole, this image is now often posted in response to a video or quote from a political figure who’s hated by the poster, in which the hated political figure says something the poster begrudgingly agrees with.

I love it because it says so much about our odd human nature, and how difficult it is for us to acknowledge that a person — or group of people — can be wrong about a whole lot of things but right about a few things.

Now, am I saying that all ideas have value and should be given the same level of respect?

Hell no.

Some ideas are stupid, some are wrong, and some are downright evil. Leaving your windows open means occasionally a bad smell will waft through your house.

But that’s the power of exposing yourself to lots of ideas. The more you take in, the better skilled you’ll become at parsing through them.

Remember that Miles Davis quote? You have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself.

The larger vocabulary of ideas, the more skilled you become at knowing which ones to apply and which ones to ignore. Like notes in a scale, some are better off left out of your trumpet solo.

Then, before too long, you might find yourself forming your very own original ideas, ones that have the power to sweep into other homes and change people’s lives for the better.

That is, assuming they have their windows open.

A right-in-time message for me, thank you!